Today marks the third

anniversary of the death of director Satoshi Kon on what would have

been his 50th year. In honour of this fact, this post will

briefly discuss the tragedy of his death, and the ways in which Kon

as a director explored the animated medium in both ingenious and

multifaceted ways.

Kon’s death was tragic

on many levels; dying at such a young age would be awful enough,

irrelevant of his artistic abilities, but the fact that he was never

able to reach his full potential as a filmmaker is perhaps more

tragic to the world at large. I fully believe that had he lived he

would have become one of the most significant figures in animation.

The word ‘genius’ tends to be excessively used these days, but I

honestly believe that, if Kon wasn’t a genius, then he

certainly would have developed into one. His films often explored the

conventions and philosophies of live-action film but did so through a

unique approach to animation. He made films that on first glance were

essentially ‘live-action films that were drawn’, replicating real

life filming techniques, treating characters as if they were solid

actors existing in a real pro-filmic space. Yet just below the

surface, it was apparent that Kon was really exploring the

possibilities of the animated image; replicating live-action only

helped to emphasise just how utterly different the animated film is

to the live-action one. But these films were not simply academic

exercises in the possibilities of animation to explore perception –

they remained engaging character-driven narratives, rarely slipping

into the realms of artistic self-indulgence. Both Tokyo

Godfathers and Millennium Actress are heartfelt

stories about characters dealing in different ways with their past

actions. The focus on both of these films is the emotional landscape

of the characters, their relationships and their memories. But this

exploration utilises the animated form completely, doubling and

fracturing the characters in order to explore their identities. Past,

present, dream, reality, individual personality and collective

unconscious all become undifferentiated in Kon’s stories, which are

always more complex than they appear on first viewing.

Another tragedy of Kon’s

death is that his final film, The Dreaming Machines,

will probably remain unfinished. Though animation studio Madhouse

announced their intentions to continue production after his death,

the film seems to have fallen by the wayside, a victim of financial

and creative issues. But most tragically of all, for me at least, is

the fact that Kon seems destined to be remembered for his two weakest

films. When news of his death first broke, the comments left up on

websites message boards over the internet reiterated more or less the

same general sentiment: ‘I wasn’t really fond of Perfect

Blue or Paprika but he clearly had the talent to grow

as an artist’. I don’t wish to paint either of these films as

‘weak’ in any objective sense, as I think that they’re both

very good in that they achieve by and large precisely what they set

out to achieve (indeed, each time I watch Perfect Blue I’m

struck by just how well directed it is – the film’s biggest flaw

is its ending… but that critique will have to wait for another

post). But neither one is as complex or rewarding as Tokyo

Godfathers, Millennium Actress or the best

episodes of the television series Paranoia Agent.

Although there is a tendency among the ‘experts’ to place more

emphasis on these less well-known films (several academic books and

journals have analysed Millennium Actress as Kon’s ‘magnum

opus’ because… well, it is), the general public will probably

always remember him for his two most obviously ‘genre’ films. If,

after his death, Hayao Miyazaki were to end up being remembered for

Kiki’s Delivery Service – perfectly good

film though it is – we would think that his memory was being

severely sold short. The same is the case with Kon.

But to demonstrate that I

do still think his brilliance is at work even in these two more

‘obvious’ films, I will now present a very brief analysis of the

complexities of image that are apparent in the opening credit

sequence of Paprika, his final finished film. Much like any

Kon film, on the surface the animation appears to be a

straightforward replication of live-action filmmaking aesthetics. The

opening five-minute sequence has two characters traverse through a

variety of overtly cinematic scenarios – homages to spy movies,

screwball comedies and Tarzan all bleed into one another – playing

like a love-letter to classic era Hollywood. But as the opening

credit sequence itself begins, we can see Kon’s more significant

concern – the possibilities of the animated image in comparison to

the live-action one – come to the fore. In a live-action film, we

see a real three-dimensional space that has been recorded and

projected on to a flat surface. But with the hand-drawn animated

film, we see a depiction of space – a flat surface that only

gives the impression of depth. This fundamental difference between

the two is Kon’s central conceit throughout the sequence.

To begin, there is an

immediately blurring between the diegetic space of the fictional

world and the extra-diegetic information of the credits. Placing the

credits within the story-world is an idea that Kon uses in Tokyo

Godfathers and each of the episodes of Paranoia Agent, and

here the names of the various people involved in the production of

the film are ‘projected’ into the world of that film. This gives

the impression that the surface of the image is actually a space

through which this light can traverse and contains solid objects that

this projected light can hit. As can be seen in the images above, the

words are themselves presented as if they are warped by uneven

surfaces, emphasising the impression of space and depth within the

surface of the image. This is of course an illusion, as the faces,

vehicles and buildings are all themselves flat depictions and the

projected words are equally flat. But the combination of the two

draws attention to this illusory nature of the animated image.

When Paprika, the titular

character riding the scooter, passes in front of a painted image on

the side of a truck, she suddenly becomes that image, which comes to

life and she blasts off of the surface into the space above the

cityscape. Again, what we have in reality is one single flat surface,

carefully crafted to create the impression of different layers of

spaces and surfaces. This in itself is common enough in animated

films. But it is Paprika’s own movement across these layers that

highlights their multifaceted nature. The image on the truck is not

simply a depiction on a flat surface, but a flat depiction of a

three-dimensional space containing a flat surface which depicts a

rocket which takes off into another flat surface depicting a

three-dimensional space.

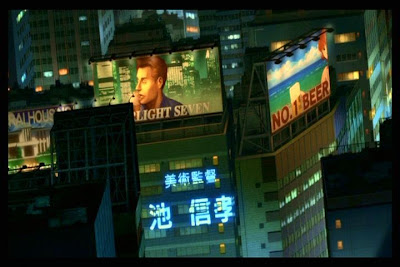

Immediately following

this we are presented another movement that creates complex

relationships between depicted surfaces and spaces. Paprika appears

as a character on a billboard on top of a skyscraper. She is depicted

standing behind a man but then decides to get up and move in to the

adjoining billboard advertising beer on a beach. She moves into the

new space, turns, reaches and picks up the glass and moves off out of

sight. The fact that the shot is composed in the way that it is,

looking down from a high angle, and the fact that the two buildings

are not aligned emphasises the games of spatial perception that Kon

is playing. We have a flat surface depicting a space containing two

buildings, the angle of which creates an even greater sense of depth.

But on top of each building are flat surfaces which depict two other

spaces. By moving across, Paprika unites the two disparate flat

depictions into a new continuous three-dimensional space. The

billboards become windows through which we can look into this

illusory-space-within-illusory-space (mirroring the way in which the

cinema screen appears to be a window into a fully-realised diegetic

world).

In the next sequence,

Paprika moves from the surface of a computer screen in to the room

containing the computer. The movement is on one level a simple shift

from flat surface to three-dimensional space, but it also, like the

billboards, creates a new space out of a surface. She is behind the

screen, but at the same time she is in front of the information being

displayed on the screen, creating a gulf between the two layers

wherein she can exist. More importantly, because of the smooth

continuity of her movement, the office space behind the partition

from which she emerges becomes collapsed into this virtual space.

Initially we have a single surface depicting an office space, within

which there are other flat surfaces, the partition and in front of

that the computer screen. But Paprika’s brief movement transforms

the image into a depiction of a virtual space containing a virtual

layer. The flat surfaces of the computer screen and partition become

a single layer in front of Paprika, while the visual information on

the computer and the office become an expansive space behind her. In

live-action, where the space would be real and not depicted and a

surface could not be a space simultaneously, such visual complexity

would be difficult, if not impossible, to pull off.

Next, Paprika emphasises

the three-dimensional space by de-emphasising herself as a flat

surface. Like the film’s credits, she is projected into the world

from somewhere else. As she skips down the hallway, unseen by the

security guard walking in the opposite direction, we can see that she

is not a solid object within that depicted space, but rather a flat

projection that warps as it moves along the different surfaces of the

hallway. She is not a flat image moving across a surface (as she is

on the side of the truck), or a solid figure moving through a surface

depiction as if it were space (as she does on the

billboards), she is a flat image moving through a three-dimensional

space. Or, at least, she is if we view the hallway as a space rather

than a surface depiction of space. Paprika’s own flatness and the

fact that she seems to move through the hallway-as-a-space

rather than over the hallway-as-a-depiction emphasises

multitude of possible ways of reading the animated image. At the very

end of the shot, she is momentarily projected over the guard, at once

emphasising his solidity and existence within a space but also

reminding us of the flatness of the surface image.

Toward the end of the

credits sequence, Paprika escapes from the unwanted amorous attention

of a couple of young men by jumping behind another man on

rollerskates. The man skates towards the camera and we see Paprika is

now an image on his shirt. As he rides into the camera, the depicted

space on his shirt becomes a three-dimensional space for Paprika. Or,

more accurately, the surface that depicts the space of the street

contains within it the depicted surface of the shirt image which then

becomes a surface depicting a new space(!). Like the computer screen

in the office earlier, the space surrounding the surface of

the shirt and the space depicted on the surface of the shirt

become collapsed into a single continuous space for Paprika. But

while in the office sequence the computer screen could almost be seen

as a window allowing us to see through the partition into the space

behind, here the notion of ‘in front’ and ‘behind’ are

rendered void. If we view the surface of the shirt as a window

through which we can see the space beyond, this means that the space

Paprika is in is behind the space of the street. The image on

the shirt therefore would be not only a window through the surface of

the shirt but also through the space of the street. So, if she starts

out in the space of the street and jumps behind the

man, how could Paprika end up behind the street? We are, of course,

not meant to think these sorts of questions of spatial continuity as

we watch – but I would like to think that this interrogation of the

animated image, as a depiction of space rather than as actual space,

is more than simply over-thinking on my part. These kinds of visual

games are at play in numerous animated films. Just think of Wile E.

Coyote painting a tunnel on to a brick wall, only for the Roadrunner

to run into the depicted tunnel, transforming the surface into

a space.

At the very last moment

before the man on skates runs into the screen, Paprika jumps to get

from one image (on the shirt) to the next (in the street). Her arms

extend beyond the frame of the shirt’s image, making it look as if

she has jumped out of the shirt. In fact, she has jumped from

the depicted street on the surface of the shirt into the space of the

street depicted on the surface image of the film. For Paprika as a

character, much like the Roadrunner, the distinction between surface

depiction and depicted space becomes redundant. She behaves as if she

knows that space is just a flat depiction on a surface and therefore

all surfaces within that depiction are fair game to treat as space.

What I have analysed here constitutes a brief three-minute opening

sequence that plays with the differences between the depiction (the

surface image) and the fiction that it depicts (the space of the

story world). These complexities exist almost entirely on the level

of image here. The rest of the film – not to mention Kon’s other

works in general – plays with this interplay in even more

complicated ways, where characterisation and narrative events are

intertwined with this manipulation of image layers, where real and

unreal, dream and memory, depiction and fiction become inexorably

bound up within the same concept.

And that is one of

the reasons why Satoshi Kon will be sorely missed.

- P. S.